Redefining AI through Collective Stewardship

Society-centered AI begins with a simple premise: the people most affected by a system should help define the problem, shape the solution, and govern its use. Rather than treating communities as data sources or end users, this approach recognizes them as co-designers, co-owners, and co-stewards of technology that touches their lives. The goal is not merely better adoption. It is legitimacy: systems that align with local values, distribute benefits fairly, and remain accountable over time.

Society-centered AI refers to the design, deployment, and governance of artificial intelligence in which affected communities share authority over problem framing, data use, evaluation, and adaptation. It extends the principles of human-centered design into collective, civic, and institutional contexts—embedding public participation throughout the AI lifecycle.

The design cycle changes when communities lead. Problem framing moves from “How can AI optimize X?” to “What is the human purpose, who is served, and what harms must be avoided?” Requirements gathering expands to include lived experience, cultural practices, and constraints such as bandwidth, cost, language, and accessibility. Data collection becomes reciprocal rather than extractive, with clear consent, transparent uses, and the option to withdraw. Evaluation focuses not just on accuracy but on whether the system strengthens agency, trust, and opportunity.

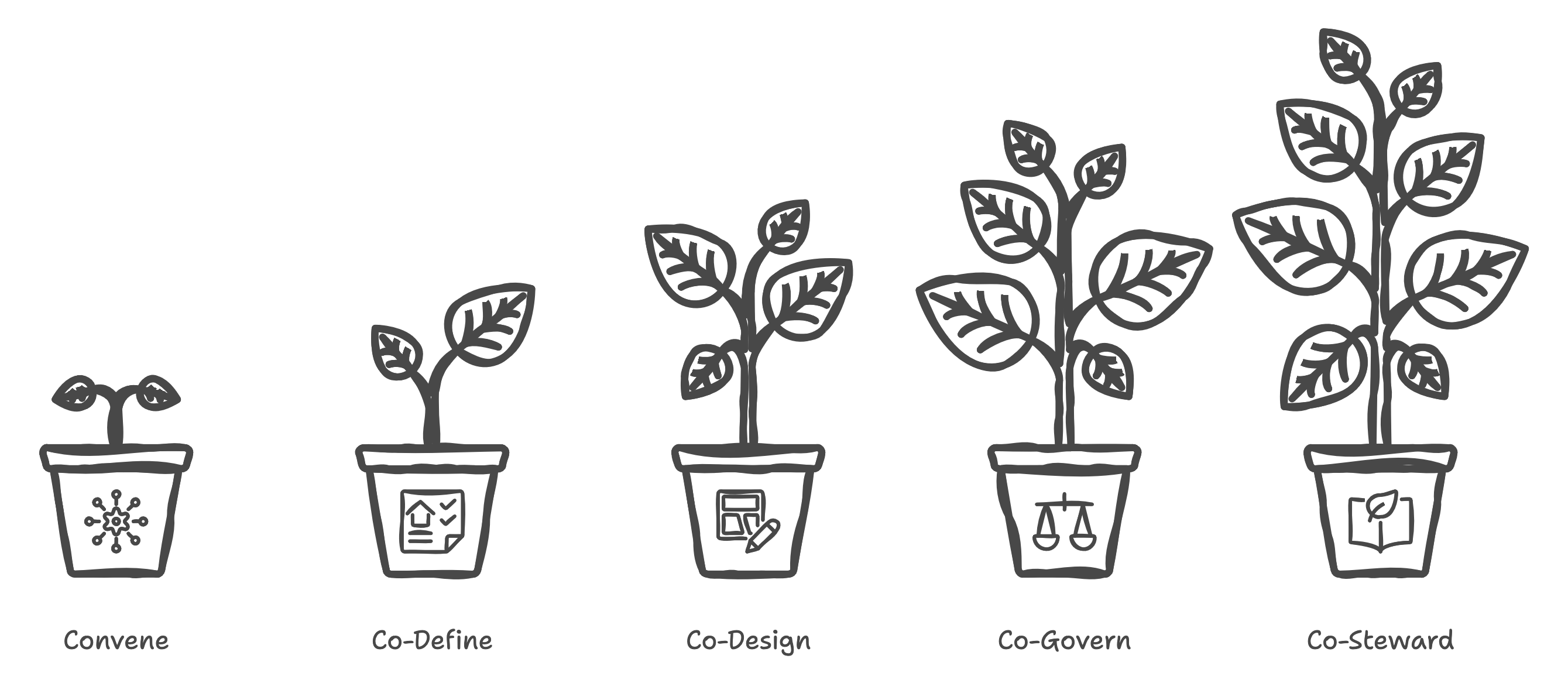

A society-centered process usually follows five steps. First, convene a representative coalition that includes community members, domain experts, implementers, and skeptics. Second, co-define goals, success metrics, and boundaries, using structured methods such as problem trees, stakeholder maps, and risk registers. Third, co-design prototypes that are testable in low-risk settings, capturing qualitative feedback alongside quantitative metrics. Fourth, co-govern deployment through participatory policies—eligibility rules, escalation paths, audit rights, and redress mechanisms. Fifth, co-steward learning, with scheduled reviews that can adjust or retire the system when conditions change.

The illustration below visualizes these five stages as a continuous, participatory cycle—showing how collective intelligence and civic stewardship guide every phase of responsible AI design.

Society-Centered AI: The Five Phases of Collaborative Design

The operational principles are pragmatic. Use plain-language documentation and multilingual materials so participation is real, not symbolic. Publish model cards and data statements that describe sources, limitations, and known risks. Implement grievance channels that respond quickly and track resolution. Share benefits: if community knowledge improves a model, the community should see tangible returns—funding for local programs, capacity building, or shared intellectual property where appropriate. Finally, measure what communities value, not only what engineers can easily count.

This approach reshapes incentives for builders. Product teams are rewarded for reducing harm, not just launching features. Roadmaps include time for community consultation, accessibility reviews, and ethics testing. Procurement favors open standards, modular architectures, and portability, so communities can switch providers without losing their data or rights. Governance shifts from one-time approvals to continuous oversight, with independent audits and public reporting.

Society-centered AI is also a posture. It requires humility about what models can and cannot do. It asks practitioners to treat lived experience as a form of expertise. It emphasizes reversible choices: default to pilots, minimize irreversible commitments, and design for graceful exits. It insists that when stakes are high—education, health, housing, benefits—humans remain at the controls for consequential decisions.

The deeper promise is cultural: technology becomes a site of civic learning. Communities practice deliberation, weigh trade-offs, and exercise stewardship. Institutions learn to share power and update rules. Engineers learn to translate technical detail without obscuring risk. Over time, this practice can strengthen the social fabric, because systems are not merely deployed; they are co-authored and co-owned.

In this sense, society-centered AI complements but extends human-centered design—embedding collective governance into every phase of the AI lifecycle. It draws on traditions of participatory design, critical technical practice, and civic technology, situating AI development within the broader field of democratic innovation.

Society-centered AI is not a slogan. It is a discipline. It replaces one-way design with reciprocal making and continuous governance. It treats communities as partners in defining the future they must live with—and ensures AI earns its place by serving that future well.